F. Frameworks

Ethics is a Key Dimension of Informed Decision Making

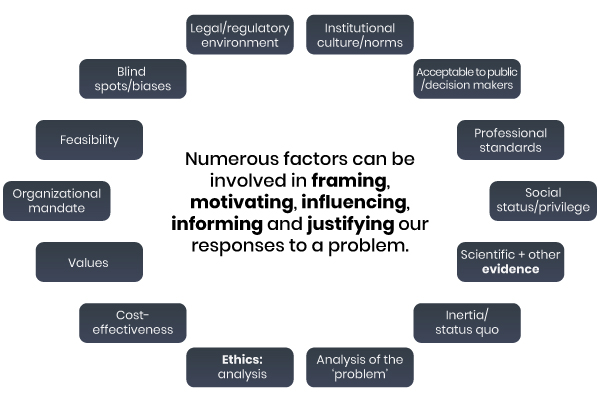

Let’s step back a bit and think about what we have to do when we confront a problem. Any problem will do, whether it is within your office, within your organization, within a ministry of health, etc. In the context of public health, when we are faced with a dilemma and must decide on a response to a problem, various factors may be brought to bear on that decision, consciously or not. These factors are involved in framing, motivating, influencing, informing and justifying our responses. Three important factors, among others, are:

- the initial determination as to whether and how something is judged to constitute a ‘problem’ (its framing, its problematization; justifying calls for particular critical attention)

- the evidence that is available to inform our understanding of the potential responses

- ethical analysis.

There are a host of other factors, such as the legal or regulatory environment, acceptability to the public, feasibility, institutional assumptions and norms, biases, status quo and so on. Other important factors are listed in the following visual, “Factors Involved in Decision Making”.

Factors Involved in Decision Making

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Complex Public Health Problem

The following is an example of a current complex public health problem in need of a solution. Ethical considerations are needed for public health strategies for optimal community acceptance and implementation to address the issue.

South_agency/E+/Getty Images

There is widespread and growing concern about the apparent epidemic of injection drug use in a community. The death toll mounts daily and there is widespread concern about how this problem might be controlled. Different groups in the community have concerns including: having family members, friends and colleagues affected, the role of local health systems in the development of addiction to pain medications, needles on the playgrounds and spread of infectious diseases such as hepatitis, and determining what might be effective solutions. Supervised injection sites and their location in neighbourhoods, the intensity of enforcement activity (e.g., war on drugs), and emphasis on and investment in population-based prevention interventions that should be deployed are all issues requiring ethical consideration when deciding on the community’s course of action.

The local health department has been given a large mandate with the recent revision of the provincial public health standards that determine activities that must be carried out locally. However, the standards also require local boards to tailor their programs and investments in them based on local needs. Yet there is now acknowledgement by senior levels of government that population health is the result of a complex system of causal factors including social determinants, environment, human biology, and health behaviour throughout the lifecycle of people living in the community. How should the organization be restructured, what capacities need to be developed and others diminished, and which issues deserve priority? These are ethical issues requiring reflection, action and justification.

We want to see ethics and evidence put to use to inform decision making. However, sometimes these considerations may be in competition with other factors that may seem more salient to decision makers. It is also worth noting that most public health decision-making environments can be highly contested and complex.

Raising Prices

djordje zivaljevic/E+/Getty Images

Tobacco pricing is a key determinant of the use of tobacco industry products, including cigarettes, spit tobaccos (chewing tobacco and snuff), cigars etc. Raising prices through taxation is seen as an effective measure – for every 10 percent increase in the price of cigarettes, there is a 3-4 percent reduction in consumption in the general population and even larger reductions among those with less disposable incomes, including children and those living in poverty. Nonetheless, there are large numbers of people who will continue to smoke in spite of tax increases and they may have less disposable income than those who quit. How do we support low-income people who are not able to quit to ensure that they have access to living necessities, e.g., food for their children, aids to cessation, and housing, if we plan to raise taxes on tobacco products?

What is an Ethics Framework?

A framework is a guide that can help to highlight ethical values and issues and serve as an aid to deliberation and decision making (Dawson, 2010b, pp. 193-200). Using a framework will involve finding a balance and making trade-offs between trying to capture every single nuance and ease of use (i.e., there is always a trade-off between perfection-seeking vs. over-simplification).

As much as we might like it to, it won’t do the hardest parts for us. Specifically, a framework can be helpful for highlighting relevant values, for raising issues and considerations and perhaps for deliberating with others about what to do, but not actually make the hard decisions.

Benefits and Limitations of Ethics Frameworks

What can frameworks offer

- They can provide an entry point and a structure for deliberation

- They can guide both specialists and novices in ethics

- They can provide a common language for addressing issues and values

- They can provide a lens for looking at and revealing ethical issues

- They can help to frame issues

What can frameworks NOT offer

- They will not do the work or thinking for you

- They will not replace your own critical perspective (they can produce complacency)

- They won’t eliminate your biases (but when deliberating in more diverse groups a framework might help reduce the effect of biases)

Characteristics of Public Health Ethics Frameworks

We now present some of the characteristics of the frameworks found in public health ethics. We start by returning to the distinction between medical or clinical ethics from public health ethics. In medical ethics, the four principles approach, sometimes referred to as principlism, first proposed by Beauchamp and Childress in their Principles of Biomedical Ethics has been the dominant approach in medical ethics ever since its first publication in 1979. Its four principles are respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice. It’s a very well-known framework, even in public health. However, it has not been readily taken up for use in public health for the reasons mentioned before, the differences between approaches and issues in medical practice versus those in public health, in addition to the population-level approach and values base that make up public health practice.

For those and other reasons, in particular medical ethics’ emphasis on individuals (and individual autonomy) and not communities, proponents of public health ethics have developed ethics frameworks tailored to the needs of public health. Since about the year 2000, many diverse frameworks have been developed for public health, but none of them became as dominant in our field as the four principles approach is in the medical field. This is probably for the best, when we consider the diversity of practices, approaches, issues and aims in public health.

Frameworks

Over the last few years, ethics frameworks for public health have proliferated. You will find a list of about 30 such frameworks here:

All of the frameworks referred to in this section may be found on this list. The list also provides links to the original documents (the vast majority are open-access); for some of the frameworks, we have produced adapted 2-page summary versions for easy reference.

Given the number and different types of frameworks available, there is a clear need for guidance as to how to choose one for a given situation in public health, and there is work to be done by users in selecting the most appropriate framework for their purpose.

Readings

For further reading on frameworks, how to use and differentiate among them, and on how to choose one, here are some resources:

Dawson, A. (2010b). Theory and practice in public health ethics: A complex relationship. In S. Peckham & A. Hann (Eds.), Public Health Ethics and Practice, pp. 191-210. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Introduction to Public Health Ethics 3: Frameworks for Public Health Ethics![]() .

.

MacDonald, M. (2015). Montréal: National Collaborating centre for Healthy Public Policy.

Public health ethics theory: Review and path to convergence![]() .

.

Lee, L. M. (2012). Public Health Reviews, 34 (1), 1-26.

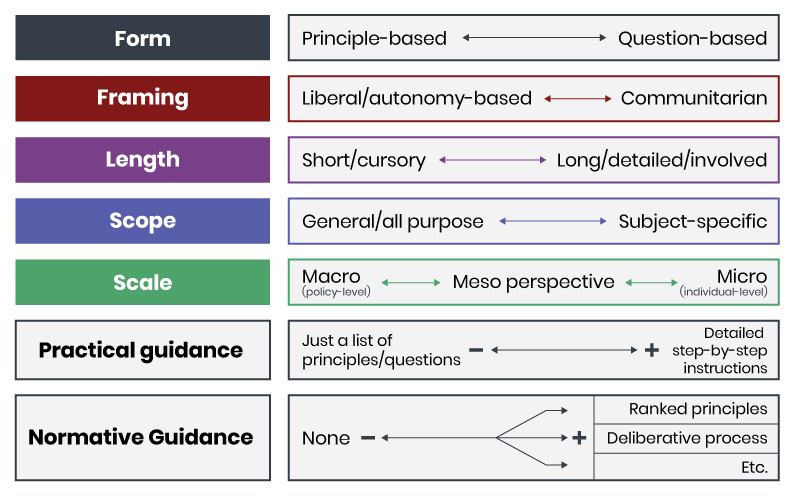

Building on the question of guidance for how to understand, select and use ethics frameworks, it is helpful to examine a range of frameworks in order to identify their main characteristics and the ways in which they differ. Doing this can help users get a sense of how a framework might function when you try to apply it in a given situation. One can identify several characteristics. Some of the main ones are described below.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

- Form

- An ethics framework might take the form of a list of principles or it may look more like a series of questions. The very influential Kass (2001) framework takes the form of a series of six questions and it does not explicitly raise ethical principles. However, the questions call upon the user to consider principles and values in responding. Other frameworks, like that of Schröder-Bäck et al. (2014) or Upshur (2002) are organized around consideration of principles. The form of a framework is not as critical as other characteristics, but it bears mentioning. Some groups will work better with some frameworks than others.

- Framing

- This refers to the underlying political orientations of the framework. A framework might place more emphasis upon a more traditionally liberal perspective by putting the emphasis on individual autonomy, or it may take a more communitarian perspective by focusing more on common goods, social justice or on communities. In choosing a framework, take note of the group with whom you are working. Maybe you are in a workplace where community values are favoured and where individualistic approaches are not held in such high esteem. However, you must also consider your broader community or region: whatever your group and its position, it has a larger public to consider. If your region has dominant individual autonomy and freedom-related (typically liberal) values at the heart of public discourse, you might consider also using a framework that places those values in the foreground in order to think through issues from that perspective. Even if you opt to implement a program that places the common good ahead of individual autonomy, using a framework that challenges your perspective will leave you better able to articulate and justify your choices, i.e., rather than only using a framework that will tend to validate those choices. Frameworks range across this spectrum from the more autonomy oriented Childress et al. (2002) to the feminist/relational perspective of Baylis et al. (2008) and the attention to social justice in ten Have et al. (2012).

- Length

- There are great variations in the lengths of frameworks and in the time required to use one to deliberate about a decision. This may seem trivial but it is important to consider how much time you have, what sort of resources are available, and to choose accordingly. A shorter document or series of questions does not necessarily limit the time you will use to deliberate, but a long list of questions addressed in a short period of time might lead a group to skim over them rather than really engage with the issues. That said, a longer framework, like that of the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (2015) might help a group to pursue finer points. Marckmann et al. (2015) is of medium length with 5 substantive values and questions, 7 procedural values & 6 steps, and Upshur’s (2002) framework is short, with four principles to consider.

- Scope

- There are also different purposes for which frameworks have been produced. Some are general purpose (Kass, 2001; Marckmann et al., 2015; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017) and are intended to be used for whatever program or policy you are considering in public health. Others have been produced specifically for issues such as responses to a pandemic (Thompson et al. 2006), interventions to address obesity (ten Have et al., 2012), surveillance initiatives (WHO, 2017), and communication (Guttman and Salmon, 2004). Some that were designed for one use might be adapted and effectively put to use in another area, but this should be done with caution. For example, the framework by ten Have et al. (2015) might make a very strong general framework for public health initiatives, but this framework was designed, tested and refined for a specific purpose and was not designed for considering the ethics of, say, a traffic-calming initiative. It may work well, but not necessarily. The main question to ask about a framework is whether using it helps to highlight the relevant values and raise the important issues in a particular case, whether it helps you to talk about those matters, and whether it helps you to work towards a decision about what to do.

- Scale

- The perspective that a framework leads you to take on an issue will vary from from micro (individual) to macro (policy) levels. Some frameworks are oriented towards individual interactions, for example respecting the rights and interests of an individual client or patient in a clinical interaction (WRHA, 2015). Most frameworks for public health ethics are more oriented towards meso- (community or interorganizational) levels or macro-(structural) level considerations (Schröder-Bäck et al., 2014; Carter et al., 2011). Their focus is on the potential effects of an intervention, program or policy upon the population, or upon certain groups within the population, particularly those who are vulnerable.

- Practical guidance

- is about how to use the framework. Some give very clear instructions about what steps to follow (Marckmann et al., 2015; Schröder-Bäck, 2012), and some just give some considerations and leave you to proceed on the basis of a list or principles or questions. There may also be implicit guidance. For example, Upshur (2002), draws on the well-established practices of principlism and in a very short paper proposes four principles better-suited to a principle-based approach for public health. Without providing much guidance, there is a traditional approach to which he appeals. In general, the ability to navigate and deliberate will involve a set of learned skills to be improved through practice.

- Normative Guidance

- is about whether or not the framework gives instructions about what to do or how to balance/interpret the relative weights/importance of principles when there is conflict or tension between/amongst them. This might take the form of principles being ranked, or guiding a group through a deliberative process to work through and to decide between/amongst them.

Ethics Frameworks

Developing the ability to select a framework for a particular situation is something that will come with experience and familiarity with the range of ethics frameworks that are available, including the ways in which they differ along the lines of the variable characteristics outlined above. For a simplified example of a situation, consider the following scenario. (This is for illustrative purposes only – in real life, there are many more factors to consider, most notably the nuances related to the program and the various populations within the region.)

Your team within the health unit are considering the implementation of a regional surveillance program relating to obesity. You want to ensure that equity is considered, as it is essential that your program will not increase inequalities by negatively affecting a low-income population in one part of your region where a high proportion of recent immigrants live. Your health unit has not systematically considered ethical issues before, and staff members do not consider themselves to be familiar with ethics tools or analysis.

When choosing a framework in this situation, you will be well-advised to seek a framework that provides what you need in terms of Scope, Framing, and Practical guidance.

PeopleImages/E+/Getty Images

- Scope

- You will want a framework that can help you to focus on the types of issues that arise in public health surveillance, like privacy, stigmatization, data management and sharing, and consent. You may seek a general framework, but you could also supplement this with considerations drawn from the ethics literature on surveillance.

- Framing

- Given the importance of reducing inequalities, you will want to have a framework that helps to you identify equity issues but that also has you find ways to engage communities, to learn what their perspectives are and how they identify what benefits them. You will likely seek a framework that focuses on social justice and on communities.

- Practical guidance

- will be especially helpful for a group with less practical experience in ethical deliberation. You might also seek some help in guiding your deliberations from someone with experience in doing so. But minimally, you will likely be better off with a framework that guides you through the steps of identifying issues and through the process of deliberation.

One framework that you might consider here is that of ten Have et al. (2012). Its focus in on obesity initiatives so it is therefore not specific to surveillance programs, but it does place emphasis on social justice/equity and provides structure and guidance. This could be supplemented by the considerations outlined in WHO (2017) which focuses on surveillance.

Ethical Issues

Ethical issues (ethical dilemmas, problems) arise when there is a situation in which one value is in tension with another. For example, water fluoridation pits common good or health maximization against individual autonomy. Some people just don’t want it but it is all or nothing. A municipality adds fluoride to the water in the belief that it is for the best overall to do so (i.e., to prevent dental caries for everyone with fluoride levels that present minimal risk to individuals) and it must do so in the awareness that for some, it will be against their autonomy (not every citizen wants fluoride in the water and yet they have no choice). Leaving the tension between health maximization and autonomy aside, an additional dimension to this is that water fluoridation reduces health inequalities because it applies to everyone and leaves no one behind.

Ethical issues can also arise when some value or principle has not been given any consideration, or given enough consideration in a situation. For example, if a health unit implements a healthy eating information campaign and a sector of the population, for one reason or another, does not take up the messages and doesn’t benefit… this can increase health inequalities and so equity or social justice might be undermined.

Some of the fallout that can come from ethical issues includes moral distress (that is, the feeling that comes from not doing what you think you should do, whether by having been blocked or having simply failed to do the right thing.)

Selecting a Framework

When selecting an ethics framework to use to examine the potential ethical issues relating to a policy, program or initiative in public health, you should select one that will: